You step out of the cramped dark tunnel and into a darker cavern, the smell of rot and decay fills your nostrils as your eyes adjust in the weak light from your torch, something moves at the far end of the room and you realize the breeze you had felt briefly was a breath. “You dare wake me?” you hear, as a claw the size of you and your dwarven friend steps down in front of you. -Roll Initiative.

That is the narrative you would have heard if you had been playing at my Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) game two weeks ago. D&D is almost forty-five years old now and one of the more passionately pursued of my hobbies. Gaming, and gamers, has recently started to become mainstream, a new phenomenon for us members of gaming culture. Throughout our short history we have been fairly content to be in the background, basking in our knowledge of the awesomeness that is our craft. This new wave of popularity scares some. They argue that it will ruin the game, that the companies are ‘selling out,’ and that the culture will not be ours anymore. While there may be more changes to come, we have endured what most industries do not. We have defeated monopolies and we have taken control from the people to give it back to corporations when they deserve it. We have even faced satanic accusations and, like any good player, we have defeated the challenges the Dungeon Master (DM) throws at us. Like any good Role-Playing Game (RPG), however, you need some back story.

Storytelling has been around for a very long time. It is possibly one of the oldest human qualities: the ability to share ideas and stories. As forms of monetary exchange became the dominant social paradigm, those who were exceedingly good at telling stories began to profit from it. Western storytellers find their history in the Celtic and Medieval bards. As Linda Alchin notes, “the Medieval bards were a distinct class with hereditary privileges. They appear to have been divided into three great sections: the first celebrated victories and sang hymns of praise; the second chanted the laws of the nation; the third gave poetic genealogies and family histories.” (2014) These bards would become replaced by what we call minstrels and troubadours.

Storytelling has been around for a very long time. It is possibly one of the oldest human qualities: the ability to share ideas and stories. As forms of monetary exchange became the dominant social paradigm, those who were exceedingly good at telling stories began to profit from it. Western storytellers find their history in the Celtic and Medieval bards. As Linda Alchin notes, “the Medieval bards were a distinct class with hereditary privileges. They appear to have been divided into three great sections: the first celebrated victories and sang hymns of praise; the second chanted the laws of the nation; the third gave poetic genealogies and family histories.” (2014) These bards would become replaced by what we call minstrels and troubadours.

Artists in the renaissance claimed this same noble bardic heritage, and were hired in a storytelling capacity to work for nobles and entertain them with tales of far-off lands and fanciful adventures. The fictionalized character of Geoffrey Chaucer gives an example of this in the 2001 film, A Knight’s Tale: “Yes, behold my lord Ulrich, the rock, the hard place, like a wind from Gelderland he sweeps by blown far from his homeland in search of glory and honor, we walk in the garden of his turbulence.” Lord Ulrich seems by all accounts poetic, well traveled, and well deserving to be there. In the movie, the people agree and cheer loudly.

Fast forward a few hundred years to the invention, and impact, of the Gutenberg press. Now the stories that were once told by bards who travelled the land, were told by printing them in a book. This allowed stories to disseminate across massive areas and break geographical boundries. Yet, as Neil Postman states in his tale of Thamus, “there are, as it were, winners and losers,” (2014, p 19) of every new technology. He uses Harold Innis’ “knowledge monopoly” (p 19) concept to show that with each new technology comes a group who wields power over the workings of the technology. Would the winners of storytelling be those who controlled the technology? Or would storytelling follow along the same path as Martin Luther saw mass-production impacting religion – removing the control from those in power and giving it to those who were reading the books (p 22). Perhaps it would become another thing entirely, to be shared and interpreted. That is what RPGs accomplished.

The history of gaming and D&D is akin to the Greek gods that gave us some of the best stories in Western culture; though young it is very incestuous. Dungeons & Dragons was first, the Cronus, created by Gary Gygax in 1974 and published under his company Tactical Studies Rules (TSR). The game was likely shaped by the culture and era that Gygax grew up in. It was a time when pulp magazines were at a peak, the history of the World Wars and the recent Vietnam War were all still very fresh in the American psyche, and miniatures war re-enactment games were relatively popular. Gygax and his friends would have many battles rolling out the great field battles of past wars. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings trilogy had been published twenty years earlier and the books had made their mark on the fantasy genre. I believe it was a combination of all these things led to the creation of the game. Like many entrepreneurs Gygax could not find anyone to publish his game, so he created TSR and did it himself.

The history of gaming and D&D is akin to the Greek gods that gave us some of the best stories in Western culture; though young it is very incestuous. Dungeons & Dragons was first, the Cronus, created by Gary Gygax in 1974 and published under his company Tactical Studies Rules (TSR). The game was likely shaped by the culture and era that Gygax grew up in. It was a time when pulp magazines were at a peak, the history of the World Wars and the recent Vietnam War were all still very fresh in the American psyche, and miniatures war re-enactment games were relatively popular. Gygax and his friends would have many battles rolling out the great field battles of past wars. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings trilogy had been published twenty years earlier and the books had made their mark on the fantasy genre. I believe it was a combination of all these things led to the creation of the game. Like many entrepreneurs Gygax could not find anyone to publish his game, so he created TSR and did it himself.

The game proved to be very popular and by the early 80s other companies were springing up to compete with and complement D&D. Two of the more prominent of these were: Hero Games, a different RPG that focused on superheroes rather than fantasy, and Iron Crown Enterprises which was created by a group of friends who were playing D&D in the Middle Earth role world. Many of these products would challenge the creative licensing of the original product and TSR would issue a cease and desist letter resulting in the offenders changing their games just enough to no longer breach the license. In 1980 the Role-Playing Game Association, RPGA had been formed “to promote quality roleplaying and to allow fans of role-playing games to meet and play games with each other.” (WotC, 2002) at first it was TSR gamers to come together and play TSR games, As part of the response to other companies the RPGA, in 1983 it was opened to non TSR games and membership increased.

In 1983 CBS picked up the rights for a saturday morning cartoon series that would run for two years. This is a point where Innis’s knowledge monopoly may have started to see reality. Not only was the tabletop game getting enough attention that others were making competing versions of it, yet now you had one of the country’s most powerful media companies interested in buying rights.

The now-defunct Dragon Magazine was also originally produced by TSR. Sevillano Pareja has a wonderful research paper about the covers of D&D Dragon magazines. It supports that by the early 80s both TSR’s D&D magazines Dragon Magazine and Dungeon Adventures had been doing fairly well among the number of fans that knew of the game and word was spreading (2012, p 506). Pareja even notes it had picked been up by the US Military as a form of creative strategizing for its officers. The department where this was the most prevalent was psychology, even drawing an officer, Roger Moore, to TSR to write as a contributor and, when his tour was done, became editor in 1983. Moore is the reason D&D Dwarves, Elves, Orcs, and Gnomes have distinctive fictional pantheons today (p 507). Moore’s vision for the two magazines, Dungeon Adventures and Dragon Magazine, would continue to have a monumental impact on the gaming world.

As the magazines began to flourish, thanks to his use of contemporary celebrity artists to illustrate the covers, it began to draw more contributors – Ed Greenwood being a prime example. This Canadian former-assistant librarian is significant because his contributions were so numerous that he would later be recognized and hired by TSR as a writer. He created the world, or “setting”, of Forgotten Realms. It remains the flagship setting of D&D to this day.

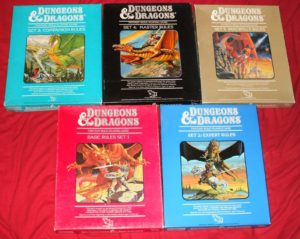

Another major change that occurred with gaming in the 80s was the creation and promotion of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (AD&D), a second, updated edition of the rules system that had come before it. AD&D fleshed out the game’s rules and provided players with more in-depth story elements. Pareja records the game was advertised in Dragon magazine Issue 142 as not just a feature, instead nearly the entirety of the issue (p 510). The AD&D starter pack and the Red Box it came in would become one of the most iconic symbols of D&D culture for the next 30 years. The edition itself would dominate TSR’s production from 1980 to 1997.

What is new is also often misunderstood and feared. A very small, very loud segment of the population (sound familiar?) in the US decided that those of us who were ‘holed away in our parents’ basements’ playing games were actually members of cults and could not, or chose not to, tell the difference between reality and gaming. In fact, my own parents did not want me to play role-playing games for fear that it would have adverse affects on me.

A comic by Jack Chick was published in 1984 (and remains in print to this very day) about the evils of D&D and RPGs. The evangelical fundamentalist still shares the comic today. The strip shows the “real side” of D&D and makes claims about the creators of the TSR game. The website stuffyoushouldknow.com has a good discussion and quick run-down of some of the more fanatical thoughts toward D&D, including Mazes and Monsters, the 1982 movie starring Tom Hanks. Now all these things have been mocked, homaged, and even embraced by those who are the targets of their criticism. There is even a Dark Dungeons film that was released in 2015.

Between 1974-1997 TSR produced over 20 different titles, some more successful than others, yet none as successful as D&D. Finally, due to ongoing financial problems, TSR was purchased by Wizards of the Coast (WotC), another gaming company that had began in 1991 and became wealthy in 1993 with its successful game, Magic: The Gathering (MtG) (WotC, 2003). In 2000 WotC would release the third edition of Dungeons & Dragons. This is when I propose that D&D, and the gaming community, took its first steps from an elitist form of art to one of popular culture.

Unknowingly, it did so in a way that challenged the idea of Frankfurt School scholars Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer when they said that those who consume must “accept what the culture manufacturers offer [them]” (Adorno & Horkheimer, 1944, p 124). Rather than maintaining a complete monopoly over the gaming systems it now owned, WotC released the Open Gaming License (OGL).

What the OGL did was akin to open source code in the computer world: the creative content of the D&D game, the Product Identity, was still protected while the mechanics of the new d20 System (the Open Game Content) was able to be used by anyone so long as they followed the OGL rules. Anyone using the OGL goes from just being another consumer of the “art for the masses,” (p 125) as Adorno and Horkheimer would say, to an early collaborating prosumer. They are no longer, simply consumers of a product, they are now also producers to the art-form within the shared system of gaming – in the same way all of us who contribute to blogs, youtube, and even facebook, are all prosumers.

The man who spearheaded the OGL, Ryan Dancy, explained in an interview in 2002, that the idea came from “copyleft” policy ideas in the computer programming industries, a movement started within the programming community to resist control being exerted over them in the early years of the internet. In his paper “Copyleft vs Copyright: A Marxist Critique”, Johan Söderberg shares that the free software community provides the first and most complete example of how a collective learning process, communication, or the general intellect becomes a producing entity in itself. Comparability rules over excludability, is a consequence of non-rival goods, because “everyone takes far more out of the Internet than they can ever give away as an individual” (2002).

How does this apply to D&D and gaming? It is certainly not all altruism, though to be fair most people who worked at WotC by the ‘90s had grown up playing the original TSR D&D or one of the rival companies’ games. WotC had spent a lot of money on its purchase and debt repayment of TSR and now they were about to launch a new system of mechanics: d20 with a system of business – the OGL. It took some convincing but eventually, as Dancy put it,

the more money other companies spend on their games, the more D&D sales are eventually made. Now, there are clearly issues of efficiency — not every dollar input to the market results in a dollar output in D&D sales; and there is a substantial time lag between input and output; and a certain amount of people are diverted from D&D to other games never to return. However, we believe very strongly that the net effect of the competition in the RPG genre is positive for D&D (2002).

However, if, as Dancy said, “The problem is not competitive >product<, the problem is competitive >systems<. I am very much for competition and for a lot of interesting and cool products” (Dancy, 2002). the question was whether the would homogenize the gaming systems by releasing the d20. Adorno and Horkheimer warn that “anyone who doubts the power of monotony [sameness] is a fool,” (A&H 1944, 148) yet Dancy’s gamble paid off. In the early 2000s D&D, and gaming, did indeed flourish under the new OGL both in ways of new products for players and sales for WotC.

In his book, An Introduction to Theories of Popular Culture, Dominic Strinati argues the skepticism of the Frankfurt school, saying, “culture has to be mass produced for [the mass] audience to be profitable” (1995, 12). It became undoubtedly profitable. There new companies and products all flooding to the OGL. In fact, for those first few years I would say it was very difficult to find a new game that was not using the d20 system. WotC also began to outsource projects to other companies to help lower their own costs. For example, publishing of the aforementioned lucrative Dragon Magazine had been sold to Paizo Publishing.

Then something changed.

What exactly happened in the upper echelon of WotC circa 2007 is still not discussed. Perhaps it was a precursor to the economic crash that was going to hit in 2008. Perhaps it was the gaming version of the problem that ended Fordism – over production and the lack of a consumer market. Maybe it was a management shift in Hasbro or WotC that just did not like to share the products anymore. Regardless of the reasons in 2007, the licensing for Dragon Magazine was up and WotC ended the contract with Paizo announcing that they were moving online, and more importantly that D&D was walking away from their own OGL. The following year WotC released its fourth edition under a new and more restrictive license. The idea was to release a system that was easier to learn and faster to play. It failed expectations. The game came out to mediocre reviews and a fanbase that felt betrayed by its loss of the OGL and a system change drastic enough to make game feel like a computer game at the table rather than what it was meant to be.

Greg Gillespie and Darren Crouse put it best when they said, “The rules-heavy approach to character generation and game mechanics in later editions slows gameplay, focuses on the notion of character builds and encourages min-maxing. The broader the perceived gap between the past and contemporary editions of the game, the greater the nostalgic yearning for products” (2012, 462).

While sales were not devastating to the company, and the system did allow for ease of introduction to new players – I personally introduced many new players to D&D using 4th ed., it did not perform nearly as well as predicted. In the space of only four years, 2008-2012, the fourth edition line ended and WotC went to work playtesting a new edition.

This 4-year period was a mini revival for systems that wanted to also come out from the d20 OGL. Paizo would become a great challenger to WotC, maintaining the OGL for all third edition D&D products, and began producing Pathfinder as a system that would remain in the OGL and would create new worlds. Paizo would even go so far as to create the Pathfinder League, a group of gamers to challenge the RPGA, which had been left behind by the new Wizards Player Network.

Starting in 2012 there has been a renaissance in Tabletop RPGs, new companies sprang into action to produce new games and systems players that were not owned or controlled by WotC. Companies like Fantasy Flight Games would put out a new Star Wars game that would present a whole new system of narrative gaming. Monte Cook began work on his Numenera Kickstarter that would get half a million dollars to create a new game. Paizo and Pathfinder would keep the fans of the OGL edition, creating a fiercely loyal fan base. Not to mention the different games & supplements that have come out in recent years from Modiphious Games, Green Ronin (pronounced ro-NEEN) Publishing, Kobold Press, and all the indie games that show up on KickStarter. Its a great time to be a gamer.

WotC reorganized in 2012 and did something radical. It went to the fans and created a massive playtest called D&D Next. For 2 years there was constant system testing. Very few announcements were made. It seemed they wanted to get the game right, and perhaps win back some of the fans that had been lost to other lines.

The fifth edition was released in August of 2014. It was simply called Dungeons & Dragons with little emphasis put on the ‘fifth’ part. Players like Gillespie and Crouse had said “AD&D highlights a rules-lite form of play that emphasizes the cleverness of the player over the abilities and skills of the character. This promotes creative problem solving and opportunities for role-play” (2012, p 462), and they wanted that back. Fifth edition provided that.

The newest edition has done well by listening to the fans and with its new system and reorganised Adventurers League, an international player group. The first of the books, The Player’s Handbook (PHB), did so well it made the 2015, New York Times best-sellers list. There are new story lines and module adventures planned for years to come. The biggest delight of the release was that the basic rules for both players and dungeon masters alike, were a collection of free-to-download pdfs. You can effectively play the new edition of D&D without paying anything or any penalties. Though if you buy the full products, you deepen your experience. There is even a new version of the OGL.

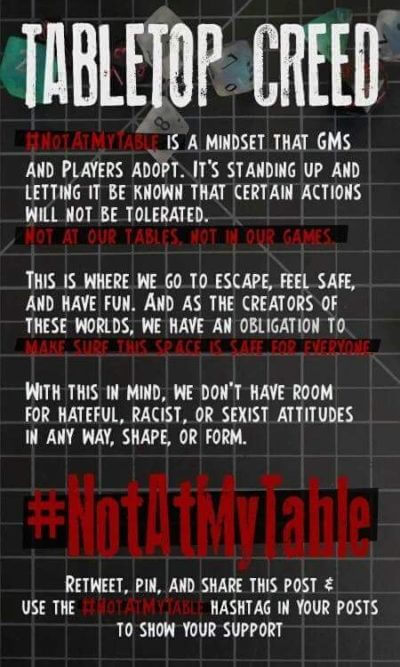

An impact that D&D 5e has had in the gaming community that should not be ignored is its new standard of inclusiveness. The Player’s Handbook is the first mainstream gaming book to offer a specific discussion on sexuality and gender inclusiveness written into its system, and the Adventurers League has strict inclusiveness and anti-hate/bullying policies. GenCon, short for Geneva Convention, was started by Gygax and his friends in his miniature days. It has become the most prolific gaming convention that was once owned by both TSR and WotC and is worth approx $50 million to the state of Indiana within which it resides. It is powerful enough that it when released a statement in early 2015 threatening the governor of Indiana to leave the state if he signed a religious freedoms bill that discriminated against gay peoples, there was cause for concern.

While this has been mostly a historical overview of D&D and gaming in a broader sense, there are further questions that, given more time to research, could be asked within the realm of Gaming and Communication. Firstly, the Marxian concept of society as being composed of a “Base” and a “Superstructure”, one built on top of and influenced by the other. In Marx’s point of view the Base is material, the Superstructure is ideological; it could be argued that the gaming industry is reversed, with the Ideological as the Base. Secondly, exploration as to whether the new OGL, or copyleft, will benefit the gaming industry, or slow down the innovation currently happening with independent game production.

For the last forty-five years D&D has existed on the fringes of mainstream culture. The gaming “nerd” community has been made fun of by two consecutive generations. We nerds have gone from being the kid who always did his homework, to the kid who would spend nights in his parents basement playing games – or messing with the occult if you listen to some. Yet today, TV shows such as Community and The Big Bang Theory both celebrate – albeit in a very simplified manner – the culture in a way that compliments it rather than insults it like the movies of the ‘70s and ‘80s. Gatherings like GenCon in Indianapolis are large enough events to stand up to governments and poor policies.

Despite the fluctuations in the markets or impacts from both corporate and grassroots camps, gaming has endured. The imagination that bore the fantasy RPG genre still is a dominant force in the gaming world. While we tabletop gamers may still hold an elitist status in some regards, new systems, new players, and new storytellers are now encouraged by pop culture and that elitism is – sometimes too slowly, but that’s another paper – being broken away.

Sure, there may be bumps along the road to adventure, none the less we will slay that clawed beast in the cavern whatever it is. Gaming is here to stay. Now, like I said before, roll for initiative.

References

Alchin, L. (2014). Medieval Bard. Retrieved March 27, 2015, from https://www.medieval-life-and-times.info/medieval-life/medieval-bard.htm

Black, T., & van Relum, T. (Producer), & Helgeland, B. T. (Director). (2001). A Knight’s Tale [Motion picture]. USA: Columbia Pictures.

Dancy, R. (2002). The Most Dangerous Column in Gaming: Open Gaming Interview With Ryan Dancey. retrieved from https://www.wizards.com/dnd/article.asp?x=dnd/md/md20020228e

Gillespie, G., & Crouse, D. (2012). There and Back Again: Nostalgia, Art, and Ideology in Old-School Dungeons and Dragons. Games And Culture, 7(6), 441-470. doi:10.1177/1555412012465004

Horkheimer, M., & Adorno, T.. (1944) Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments. Stanford: Stanford University Press [“The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception”: 94-136]. 119-167.

“The History of TSR”. Wizards of the Coast. Archived from the original on 2008-10-04. Retrieved 2015-03-27.

Postman, N. (2014). The Judgement of Thamus. In G. McCarron, Introduction to Communication Studies (3rd ed., pp. 16-24). Boston MA: Pearson Learning Solutions. 16-24

Schnoebelen, W. (2015). Straight Talk on Dungeons and Dragons. Chick.com. Retrieved 27 March 2015, from https://www.chick.com/articles/dnd.asp

Sevillano Pareja, H. (2012). History of a Journal: the Case of Dragon Magazine (U.S. Edition). El Futuro Del Pasado, 3, 503-521. doi:10.14516/fdp

Söderberg, J. (2002). Copyleft vs. Copyright: A Marxist Critique. First Monday, 7(3). doi:10.5210/fm.v7i3.938

Strinati, D. (1995). An introduction to theories of popular culture. London: Routledge.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks